Citizen Writes

Research hot topics

Changing job demands during COVID-19

2021-07-21

By Professor Stephen Wood

Job demands in universities have increased during the pandemic. This is the result of my latest analysis of my study of university staff, academics and non-academics. My study has involved staff in two universities in England, who have completed surveys in at eleven points in time from May 2020 to February 2021.

Analysis of the time series has revealed an increase in job demands, for which we have a variety of measures. These include:

- a self-report rating of workload based on assessing if it was over the previous seven days (on a five-point scale) from “far too little” to “far too much”;

- a scale of work intensity, based on questions such as “I never seem to have enough time to get my work” and “I was asked/needed to do an excessive amount of work”;

- the total hours worked during a week (including weekends).

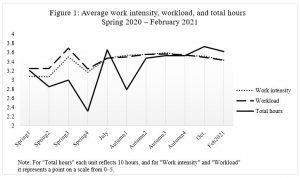

All these indicators increased over the pandemic, especially after May 2020, and tapered off a little between 2020 and February this year. This is clearly visible from Figure 1.

The average of the workload intensity measure was 3.08 in the first week of our Spring diary study and rose to 3.48 in July and to 3.68 in the Autumn. 31% reported that their workload was either too high or very high at the beginning of the study, a figure that rose to as high as 48% in Autumn.

A key contributing factor to the increased job demands is likely to have been the adjustments required for online teaching. Our analysis revealed that employees whose job content and workload were most affected by blended learning had higher levels of work intensity.

Other factors that appear (from the responses in the open text box at the end of surveys) to have contributed to the increase in demands include:

- initial adjustments to working at home, for example learning Teams and other communication processes for online meetings and establishing IT facilities and home working areas;

- covering for reductions in staff due to absenteeism, redundancies or restrictions on recruitment;

- changes to deal with the pandemic, for example through having intakes in both September and January, students having specific concerns about their well-being or course material or their use of mitigating circumstances for late submissions of assessment;

- spending more time on screen with its potential to create headaches, eye strains and musculoskeletal problems, and on-line meetings may have effects beyond this as the cognitive load may be higher than in face-to-face conversations (what has acquired the label Zoom fatigue).

People appeared to have made a range of accommodations to meet these increased demands? Figure 1 shows that increasing working hours was one of these.

Other accommodations included working more hours over the weekends, working over Christmas, and not taking lunch, mini-breaks or a normal summer holiday. These were all correlated with work intensity.

As the pandemic progressed there was some discussion of how some employees may have extended their working day. For example, parents with child or other care responsibilities may return to work in the evening having earlier been involved in home schooling and other domestic duties. The extent of the working day beyond a 9–5 routine was correlated with work intensity.

People with high job demands were also likely to feel their ability to exercise was constrained by their job demands.

Our key employee outcomes were significantly affected by job demands: well-being, work–nonwork conflict and cognitive stress (difficulty to make decisions, with remembering or thinking clearly). The higher the level of work intensity the lower the well-being and the higher work–nonwork conflict the cognitive stress. The explanation for some of the well-being increase was indeed the increase in work–nonwork conflict, and particularly work-to-nonwork conflict.

The increasing job demands do not appear to have discoloured people’s views of homeworking. 80% of respondents in October said they were somewhat or extremely satisfied with homeworking. This did, however, decline to 70% in February 2021.

The two most significant influences on homeworking satisfaction have negative effects on it: these being loneliness and divergence from normal work. Job autonomy had a positive effect. In February 2021, people who lived alone had lower levels of homeworker satisfaction than others, which had not been the case in 2020. Also, IT issues as a constraint on working at home reappeared in February as an important source of dissatisfaction. While those with long commutes were more satisfied with homeworking.

s.j.wood@le.ac.uk; 07717377815