Citizen Writes

Research hot topics

Onwards to the Ice Giants

2021-07-06

By Dr. Leigh Fletcher, Planetary Scientist

Over the past two decades, Leicester planetary scientists have had the privilege of being involved in cutting-edge missions to explore the distant worlds of our Solar System: from the triumph of Cassini’s 13-year exploration of the Saturn system, to the breath-taking insights from NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter, to the highly-anticipated glimpses of the distant Solar System by the James Webb Space Telescope. We’re playing key roles in the next big mission to explore Jupiter’s collection of moons – Europa, Ganymede and Callisto – with the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, launching next year. But there are two distant, frigid, and lonely destinations that have so-far eluded us.

Beyond Saturn lies the realm of the Ice Giants, Uranus and Neptune. Visited only once by Voyager during a ‘golden era’ in the 1980s, using rapid flybys of spacecraft built with the technology of the 1970s, these worlds represent the “frozen frontier” of humankind’s exploration, the only major class of planet yet to be visited by an orbiting spacecraft.

What little we do know about these Ice Giants presents a tantalising wonderland for planetary scientists – systems that require the entire arsenal of physics, chemistry, geology, meteorology, plasma physics, and many other disciplines to fully understand. These worlds are smaller than the Gas Giants (Jupiter and Saturn), at around 4 Earth radii in size, so they sit in between the rocky planets and the larger giant planets. They rotate more slowly than the Gas Giants, and have atmospheres that are heavily enriched in materials that originally derived from ices and rocks accreted during their formation. Hence the name “Ice Giant,” which (somewhat confusingly!) doesn’t actually mean they’re made of ice, although it’s hard to be sure what all the water is doing down at the crushing pressures and temperatures of their hidden interiors. There might actually be as much rock as ice, we just don’t know!

Uranus and Neptune possess magnetic fields that are quite unlike anything seen elsewhere in our Solar System, offset and tilted compared to the planet’s rotation. In Uranus’ case, the enormous axial tilt (Uranus rolls around the Solar System on its side, with a 98-degree tilt, maybe due to some gargantuan collision in the distant past) means that the magnetic field interacts with the solar wind in a completely unique and time-variable way. Uranus’ tilt also results in bizarre seasons, with each pole spending four decades in the darkness of polar winter, before four decades in bright sunlight.

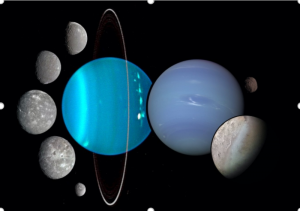

Figure 1 Showcasing the Uranus system (left, with the collection of five classical icy satellites) and Neptune system (right, with Triton to the lower right).

Those seasonal extremes affect the Uranian clouds, which are made of ices of methane and hydrogen sulphide, the gas responsible for the smell of rotten eggs. A few years ago, I was part of a fun study using the Gemini telescope that actually revealed direct evidence of hydrogen sulphide above the Uranian clouds – cue much school-boy humour, but a news story that keeps coming around again and again.

The planets are attended by rings and a diverse collection of icy satellites. Uranus’ moons are thought to be a natural satellite system, with evidence of resurfacing and geological activity, maybe suggesting the presence of internal oceans beneath thick icy crusts (we call these Ocean World candidates). Neptune’s satellite system has been completely disrupted by the cuckoo-like arrival of Triton, a Dwarf Planet captured from the Kuiper Belt, and a fascinating world in its own right, with an icy surface, thin atmosphere, and active plumes erupting from a chaotic, jumbled surface.

For all these reasons and more, planetary scientists see a journey to Uranus and/or Neptune as the next logical step in our exploration of the outer solar system. We’re dreaming of sending a sophisticated orbiter and probe to one of these Ice Giants, making use of Jupiter gravity assists to get us out there in a timely fashion. Windows of opportunity come around every 12-13 years, with the next best shot being in the early 2030s. That means we have to start designing and building our mission now. The scale of the challenge is immense, not least because we rely on radioisotope decay to provide power at such great distances from the Sun. It’s almost certain that international partnerships between a number of agencies, especially ESA and NASA, will be needed to achieve our goals.

In 2019, I led a proposal to ESA for an Ice Giant mission as a cornerstone of their strategic planning in the 2030s-2050s time frame (known as Voyage 2050), alongside several Leicester and UK colleagues. The recent ESA report supports our efforts for an international partnership mission, although Europe can’t go it alone. In the months before the COVID-19 pandemic, I hosted an international workshop on Ice Giant System exploration at the Royal Society in London, attended by more than 200 scientists, engineers, policy makers and industry experts, all united in the goal of seeing a mission to the Ice Giants.

All eyes are now on the USA, where a wide-ranging survey of planetary science priorities is now underway, aiming to shape NASA’s strategy for the next decade. Leicester scientists, myself included, were part of the Neptune Odyssey (orbiter and probe) concept studied as part of that survey. Whatever the outcome, we hope that an ambitious mission to an Ice Giant is at the top of that list, and that Leicester researchers will continue to play a leading role in the exploration of the cold, distant reaches of the outer Solar System.